Why you’re getting this: You subscribed to an email list on my website or followed this Substack. You can unsubscribe at any time, and I won't be upset. I won't even know!

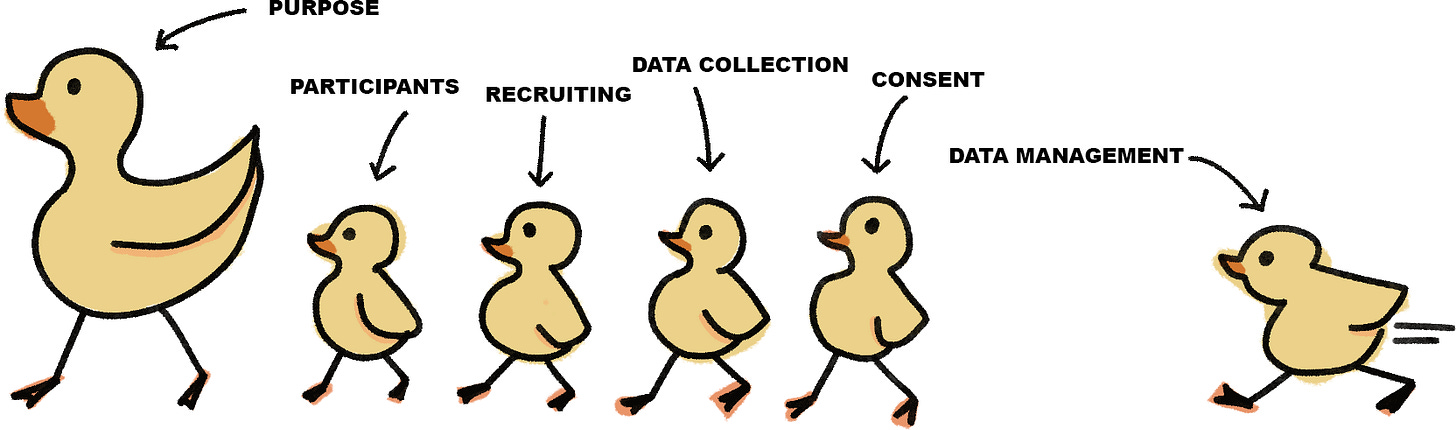

In this issue: I write about how the IRB protocol, while a lot of work, helped us get our ducks in a row for the Listening Tour. I end with a moment of noticing while visiting Meta HQ last week.

RECAP!

Last week, I wrote that our IRB (Institutional Review Board) protocol would be "finished, goshdarnit," and I am pleased to report that it is.

WELL, SORT OF.

I’ve submitted it. Now, the review board'll read every last one of the 80 (!!) pages, ask questions, and offer recommendations to ensure that what we're planning to do is ethical and minimizes any risks the research participants might face. In the very best-case scenario, it'll take a couple of weeks, but given the complexity of what we've proposed, it'll probably take longer.

As I mentioned last week, IRB, short for "Institutional Review Board," is a step in every research project. IRBs began in response to some seriously unethical research practices, and have evolved to regulate all manner of research, including the kind we’re doing on the Listening Tour. The best thing about IRBs is that they protect research participants. The next best thing is they require researchers to get their ducks in a row before we begin our research.

Most of the research I do is qualitative. This means that I try to understand how people think or feel about something by talking to them about their experiences and behaviors. These conversations usually happen in the context of an interview or focus group, but sometimes I make observations, host workshops, or even ask people to create artwork about how they feel. Whatever the method, the data I collect include ➊ what they said (e.g., transcripts and recordings), ➋ what they made (e.g., photographs and screenshots), ➌ and what I noticed (e.g., research memos — more on this in a future issue!).

Once the data are collected, I use empirical research methods (translation: I follow specific steps widely used by others and shown to be effective). My favorite methods are ones that recognize the biases researchers bring to our analyses. We all have lived experiences that influence how we see the world. Things like where we grew up, who raised us, the sex we were assigned at birth, the economic resources we did or didn’t have, etc. As researchers, those experiences not only influence how we see the world, they influence how we analyze our data, too. Part of having rigor as a qualitative researcher is deeply understanding those influences, accounting for how they impact your analyses, and communicating them clearly in the context of your findings.

Aside: I'm sensitive to how much jargon researchers use to describe what we do. I want to be accurate, approachable, and not too overly explainy. Thanks for your grace as I figure out how to walk this tricky line, and let me know what you think!

GETTING QUACKING

Getting the Center’s ducks in a row for the Listening Tour means figuring out:

What we want to know (purpose).

Who we’re going to study (participants).

How we’re going to find those people (recruiting).

What we’re going to do together (data collection).

How we’ll make sure they understand what’s happening (consent).

And what we’ll do to protect their privacy (data management).

The level of care we need to apply in each of these areas varies based on how vulnerable the participants are and what kind of data we want to collect about them. Some people are inherently more vulnerable than others due to power dynamics, cognitive abilities, and/or socioeconomic circumstances. For example, if you want to conduct research with teens (which we do), you have to do more to protect them because they are still growing and developing. We can’t know for sure if they’ve thought of everything if they say yes. This is why it’s typical to get consent from parents or guardians when doing research with teens.

HOW RISKY IS A LISTENING TOUR?

To the best of my knowledge at this moment, not very. But that doesn't let us off the hook. And it becomes less and less risky every step we take to protect the data we’re collecting and to make sure the folks we’re collecting that data from are aware of what's happening.

The reason why our IRB protocol was so gnarly is because the Listening Tour involves a bunch of different ways of collecting data:

Public events: We want to be able to jot down notes at public events about what adults say about thriving with tech.

Casual convos: We want to be able to chat with adults at the dog park, on the train, or in line at the grocery store about their tech habits and opinions.

Actual interviews: We want to be able to ask adults the questions we’ve been workshopping.

Youth group programs: We want to run youth group programs where teens think together about digital thriving.

Actual interviews and focus groups with young people: We want to schedule time with teens for interviews and focus groups.

The IRB will help us figure out if we need to announce 🙋 our presence at public events. If we’ll need to get consent 🖋️ before talking to someone at the dog park. And how to make sure teens in a youth group that don’t want to participate 🙅 have that option and don’t feel singled out doing so.

While I playfully lament it, the IRB process is actually quite helpful. It turned the idea of “let’s talk to people about digital thriving” into the pathways above. It invited us to figure out, with an exceptional level of detail, precisely what we’ll do. At their best, IRB protocols are more than a forcing function for getting your ducks in a row. They give researchers a reason to be thoughtful about what we plan to do, and they compel us to do so with as much care for our research participants as possible.

WHILE WE WAIT

You’ll be nearly the first to know what happens next with the IRB. Until then, I’ll be writing up my experiences last week with folks at UC-Irvine’s Connected Learning Lab and how a Clint’s Circle hosted at Social Science foo camp taught me an unexpected and somewhat challenging lesson. More soon!

p.s. I’ve been noticing hearts for almost 10 years. Here’s an exquisite find on Meta’s Menlo Park campus last week:

I am so enthused that you explain the jargon swirling around this project. I really have an issue with jargon. It is clear that you want everyone to understand what you are saying. Making the effort to explain jargon is a beautiful expression of how much you care about your readers. Your writing is clear and understandable and the part of you that recognizes the need for explanation will resonate beautifully with your research participants.

Excellent review of the qualitative process and IRB's! Thank you Beck!